Today’s Place – In conversation with Johan Pas,Thom Puckey, Walter Van Beirendonck and Ronald Stoops

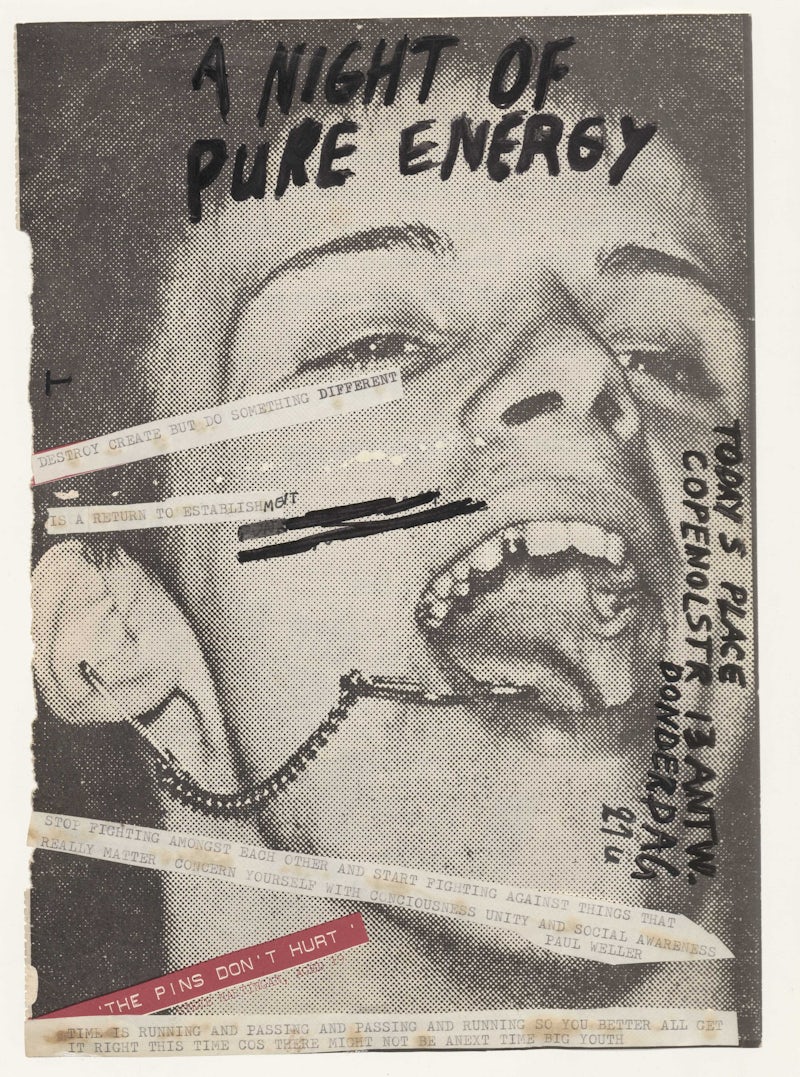

The 80s are often presented as the era of postmodern individualism, but even during those times alternative artist initiatives with a social character emerged. In the context of political negligence and a lack of structural policies, artists took matters into their own hands. One of such initiatives was Today’s Place, created in 1977 when Jan Janssen and Rudolf Verbesselt squatted an empty building in Coppenolstraat. Prompted by Narcisse Tordoir, this space grew into a radically multidisciplinary meeting place where art, performance, fashion and music intersected. Although many of these ventures were fleeting and experimental, their impact remains tangible in the careers of those involved as well as in the broader art landscape.

On the occasion of the archival presentation Today’s Place (14/02/2025 – 11/05/2025), M HKA interviewed four guests who were involved or feel an affinity with the spirit of the time: Johan Pas, Thom Puckey, Walter Van Beirendonck and Ronald Stoops. We spoke with them about their personal experiences and the impact of such an artistic sanctuary.

“Johan Pas — Professor of Arts — Head of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp ”

Can you introduce yourself?

My name is Johan Pas. I am an Art Historian and I mainly research how artists, over time, have mediated their work through exhibitions, self-organization, through publications. So I’m very much interested in art, but even more so in the way art has reached people throughout the 20th century up until this day. And artists have actually always taken a very radical position in that regard. I often tell my students that avant-garde art is about the fact that artists took the initiative themselves. The first exhibition of the Impressionists is a good example of that.

Other than this, I am also a collector. I collect printed matter by artists from the 20th century, especially from the ’60s and ’70s, including from the punk movement. In addition, I am someone who has been working in art education, all my life actually. I taught art history, modern and contemporary, for many years. Since 2017, I have been the head of the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp.

You’re mentioning artists taking on radical positions. Why do you think Today’s Place was created, out of which necessity?

Some former students of the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, particularly Jan Janssen, Rudolf Verbesselt and Narcisse Tordoir, had met in the Academy, and like many students there were a bit frustrated with the very classical training they received there, which was still very much in line with early 20th-century traditions, so they decided to work together.

In that sense, Today’s Place actually answered the necessity in that they needed a hub, a platform to be able to organize things that they couldn’t organize elsewhere, but, in addition, to show things that they themselves could not get shown in the gallery circuit – they were young artists – and, thirdly, to invite like-minded people by organising concerts and offering drinks.

It is notable that in Antwerp, almost every generation of young artists comes out of the Academy with some kind of frustration, forges connections and then organizes things in public or semi-public spaces.

At that point, Tordoir, Verbesselt and Janssen also really distanced themselves from their classical training by getting interested in performance, active things, not showing classical artworks but actually doing things on the spot. The slogan of the punk movement in the second half of the 70s was No Future. And in that sense, the name Today’s Place pretty much answers to that slogan as well: No Future, Today. What happens today, Today’s Place, what happens right now is important.

So in that sense, Today’s Place is a kind of punk place almost. Not only because of the fact that they organized punk concerts such as those of The Kids and Stalag, but also the fact that they did it all by themselves. Do-it-yourself, self-organization, in a raw, rough, direct, not low, but no-budget way. And that makes that place perhaps the first and possibly also the last punk spot in Antwerp.

In what ways do you think that particular zeitgeist contributed to Today’s Place?

Punk is mainly known as a music movement, but punk was more. Punk was actually very interdisciplinary. It included DIY fashion, graphic design, think of the punk zines that were photocopied, but performance was also typical of punk, namely using one’s own body as a working material Today’s Place actually covered all those disciplines, and the boundaries between them were in fact very blurred. It is also distinctive that Tordoir, who had trained as a painter, was very much into performance, only to then actually return back to painting during the 1980s, but in a completely detached way.

You’re a collector of archival material yourself. Why do you think it is relevant to revisit Today’s Place through this presentation?

It is very interesting to look at and display this archival material of Today’s Place, coming from Narcisse Tordoir. Firstly, because such archival material shows the ways in which artists in that period communicated about their work. The aesthetic of that material is typical of the zeitgeist. It’s black and white, it’s photocopied, it contains bright red rubber stamps. It has a pretty aggressive in-the-face look and feel, which is very much back in style today in the world of graphic design. This whole DIY, non-digital form of communication appeals greatly to younger generations.

In addition, Today’s Place documents a kind of artistic practice that is critical, political, ideological and activist. In times such as the present, when everything appears to be in shambles and there are a lot of uncertainties, it is very important for artists to see that it is possible to take a stance and resist in a very radical way. And that’s what Today’s Place did in 1977, but what may also be particularly relevant today.

“Thom Puckey — Artist, ½ of Reindeer Werk ”

Can you introduce yourself?

I’m Thom Puckey. I live in Amsterdam, but I’m English. I’m now a sculptor, doing different sorts of art work, but I came to Amsterdam as a performance artist, together with my friend Dirk Larsen. We met each other in London, at the Royal College of Art, in the Stone Age, let me see, that would be 1972. And then I saw his work and he came to me and said: Have you heard about this new art form which everybody’s doing, which I’m doing too, it’s called Live Art, Performance Art.

Together with Dirk Larsen, you formed the performance duo Reindeer Werk. How did this came about and what did your practice look like?

We built up a very difficult reputation at the Royal College of Art. We were the sort of bad boys of the school, and we decided only to use the school as an office to organize shows for ourselves outside of the school.

My mother was having a lot of mental struggles and got put into a mental hospital and I went to visit her every other day, and I noticed that a lot of the people inside the hospital were behaving the same way as we were behaving as artists. So they create their own bubble of their own behaviour, which is seen to be very shocking by normal people on the streets. In a way, we set up a similar structure when we went to art centres and places to do our work, to do performances. We made the bubble, and you had the people who were looking at it. It set up an incredible sort of tension in the air.

We were not aggressive, neither to each other, nor to the audience, to the people. But we were very extreme in what we did for and to ourselves.

We liked it more in Holland and Belgium than in England, and we were blacklisted by the British Council, so we weren’t allowed to have any more money because they had seen our performances in Denmark and were so shocked that they blacklisted us, so we just moved to Holland.

How did you eventually end up in Today’s Place? How did those relationships came about?

In 1975 we were invited by Roger D’Hondt, who’s a known figure in Belgium, to come and do a performance at his center [New Reform], in Aalst. But when they saw us [Narcisse Tordoir and Jan Janssen], when they saw our work, our performance, evidently something clicked and something changed, right? And we didn’t only form a very firm friendship, but we also formed a sort of artistic friendship, in the sense we could identify with each other’s works.

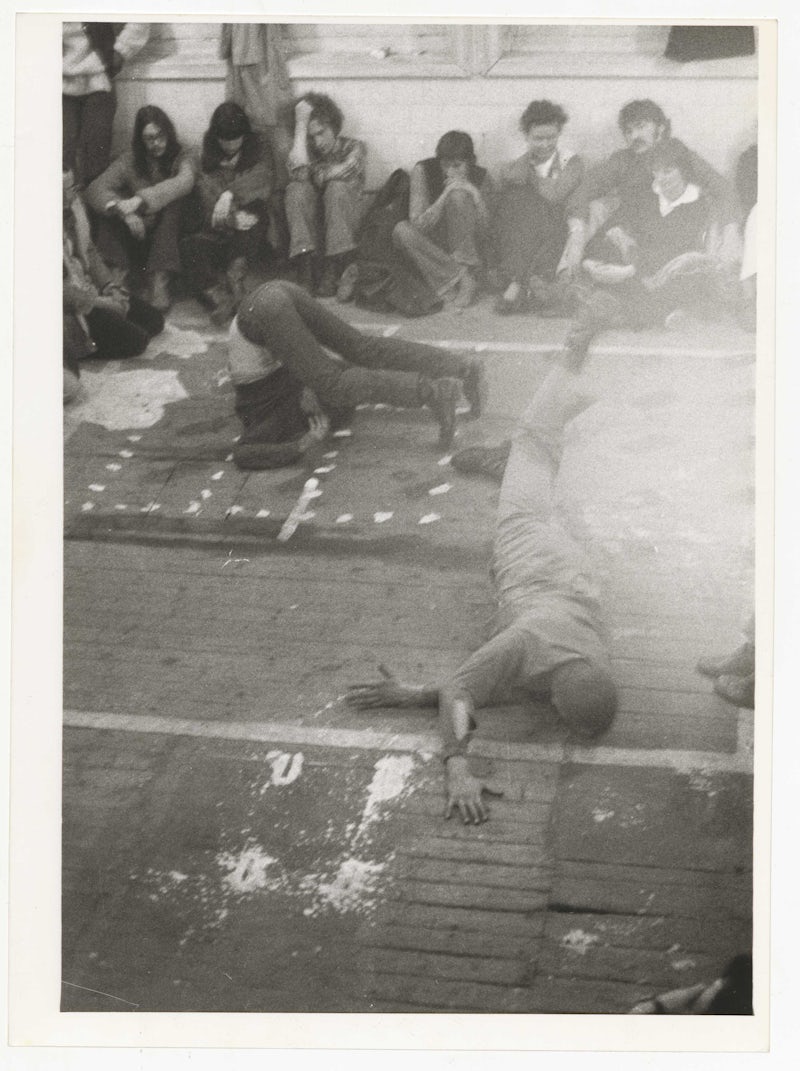

Narcisse invited us to come and do a performance at Today’s Place. Today’s Place was structured like a podium, like a lecture hall, almost that you had the stage at the bottom, and then you had the rising part of the back, and then Narcisse stood at the back to take photographs at regular intervals of our performance. We were throwing around lots of money on the floor. We were doing our normal sort of ‘behaviour’ performance. And we were operating on the floor. Almost said stage, but on the floor. Independently of each other, in the sense of not contacting each other, not sort of touching each other, but with a very firm sort of interaction between us, which we got used to by then.

I think what Narcisse and the others especially liked was the way that we were muddying the gap between art and life. And that’s what they were doing here as well with Today’s Place. The sort of cross-over between the two things as if to say, well, maybe it is the same thing. Maybe art is life and life is art and maybe it should always be like that.

What was your impression of Today’s Place?

I must say we were very impressed by what they did there. They did not just host us, but also other performance artists and filmmakers from England.

They were a very busy, very fantastic underground art space which depended, which ran on the energy, which came from people like Narcisse [Tordoir], and from Jan Janssen, from Bruna [Hautman], from Ronald [Stoops], and from the others. It was their energy, the investment of their energy in the space which made it such an active place.

I think it’s important that people know about it, especially because for a long time, it was not known about. Maybe it’s only now, looking back, how wonderful that was and how we’re never going to have that again, or maybe it can have an influence. I mean, look, we have a thing like Today’s Place, which was happening in a squatted building, in trouble with the police, in trouble with the landlord. A very good name amongst young people, many of whom had no idea about contemporary art, but who were very much interested in the mixed bit of the cultures.

“Walter Van Beirendonck — Fashion Designer ”

How do you remember Today’s Place and how did you end up there? As it happens, you are younger than the rest of the group and were just starting college.

That’s right. I mainly ended up in that friend group. I actually went straight to the Academy in Antwerp after boarding school. So that was a very big clash really, a very big discovery as well. I did a preparatory year first, before I started fashion training, and in that year I came into contact with Narcisse [Tordoir]. He came to give a trial class in the grade I was in. And I had a box of materials and there were all these pictures of Bowie glued on to it. And that really was our contact, David Bowie. I then became very good friends with Narcisse and Bruna [Hautman]. I also remember that just when Today’s Place started, we went on a trip to the Biennial together. So they also helped me get to know the art world a bit.

The archive presentation features images of you that were shown in Today’s Place. Can you tell a little more about this?

At some point, I don’t even know why, I had the idea of creating my own kind of performance. Rabbit Virility was the name. It’s kind of based on a trauma of mine. I began to make some images with two real rabbits, but also with one dead rabbit. Those were literally made with a self-timer in my parents’ spray booth in the garage. It was a very weird setting, but I really enjoyed doing these kinds of creative things. I found that very fascinating to do, the setting, the staging, the makeup. I had done everything myself, so it was a complete concept. At a certain point Narcisse saw it, and he said it would be great if we could project it. I then agreed but with a lot of stress, because I didn’t feel like that right away…I also didn’t have the ambition to become an artist, I was still involved with fashion. And then after the projection, questions suddenly came up and I wasn’t ready at all, so that was a very weird moment. And I simply said ‘no comment’.

So, you were mostly involved with fashion. To what extent was fashion a part of Today’s Place and the people who attended?

In some way, the whole group was also very involved with clothing and fashion. And, of course, we had the phenomenon of Bowie and also a number of artists at that time who appealed enormously to our imagination with their clothes.

Ronald [Stoops] literally made plastic trousers during that period, and they were then worn by us. Dirk [Van Saene] had one of those trousers from Ronald. Together with Bruna, we had also found a manufacturer of jumpers. We had huge jumpers made there, oversized ones. We were involved in things like that because we found that to be part of the whole adventure, that adventure of art, music and fashion. It was really something that was very much intertwined.

I especially found the impact and what you got to see that was quite intense at times, I think that was mainly what stuck with me the most too. That it was really harsh at times.

Today’s Place was part of those years of my development and my discovery. And of course it was fantastic to see how you could set things up with very little resources, with a lot of ambition. It was also an incredibly dynamic group of people, and meeting them certainly marked me on a friendship level, but it also of course gave me the strength of carrying on, it stimulated and motivated me enormously.

We were engaged in that kind of thing because we thought that was also part of the whole adventure, that adventure of art, music and fashion. It was truly something that was very much intertwined.

I think it’s just important that people, and young people, know about times when things like this could happen and about a certain freedom, because in the end, it’s mostly about freedom. It’s about an ambition of a bunch of young people who also wanted to make their own future, or who really wanted to go for it, and that’s an energy that’s hugely fascinating to young people as well. So I think it’s very good that it’s here physically and that it can inspire and motivate people.

“Ronald Stoops”

How did you end up in Antwerp?

I actually lived in London and I had a store in The Hague, along with some friends of mine. We regularly went to Antwerp to buy clothes from the Salvation Army. On New Year’s Eve, I came here to celebrate and I met a woman, and I moved in with her after six months. She lived in Antwerp, therefore I lived in Antwerp. So I met a lot of people actually, all from the Academy. We would go to pub De Skipper to play ping-pong and have beers.

What was your role in Today’s Place?

I mainly did the music. We played a lot of reggae. Jacques Chapon, do you know him? He introduced the first Reggae record in Antwerp. He would go to Jamaica and get records there. That was done a lot. People from that Antwerp all went to Jamaica. Buying records and going out.

I would be playing and there would be crates of beer you could buy. I don’t think we ever made a profit. It was really just to entertain people, in a different way. We did have to charge entrance at one point because the police had demanded it. So what did we do? You had to become a member, but for that membership fee you got free drinks. So that was a null operation. But that was the intention. We didn’t want to make money at all. We just wanted people to have a good time and feel something different. Something they were not familiar with.

It was completely different from any other place. It wasn’t a bar, it wasn’t a nightclub. It was just a place where loud music was played and you could smoke, you could go outside there. There was no doorman at the door. Nothing. It was really more a place where you could get to know people who thought in a certain spirit, a little alternative, young.

It was a white space. That was nice, too. White, TL’s on the wall. That was really new. And there was no cozy atmosphere created, that was also the intention. Not that it was so heavily thought about, mind you, it wasn’t that conceptual at all, but it just was the way it was, and apparently that was attractive.

You told us you mainly did the music in Today’s Place. When did your interest for photography start?

I got started because of Walter [Van Beirendonck]. At one point Walter said we needed photographers, but we didn’t have any. And that way I had work right away. I said okay. At the time, it was a protected profession, so you had to have a degree. I then started evening school. Those teachers did not think it was funny when I was already working for the magazines. I said, ‘Look, I did all this’. They didn’t like any of it. It’s funn, though. So yeah, I actually got started via Walter.

Today’s Place can be visited in M HKA until 11 May 2025. The presentation was created in close collaboration with artist Narcisse Tordoir, whose archive M HKA received with much gratitude.